The House Science Committee inserted itself into a multi-state investigation of oil industry titan Exxon Mobil on Wednesday — issuing unprecedented subpoenas to the Attorneys General of New York and Massachusetts as well as eight environmental groups.

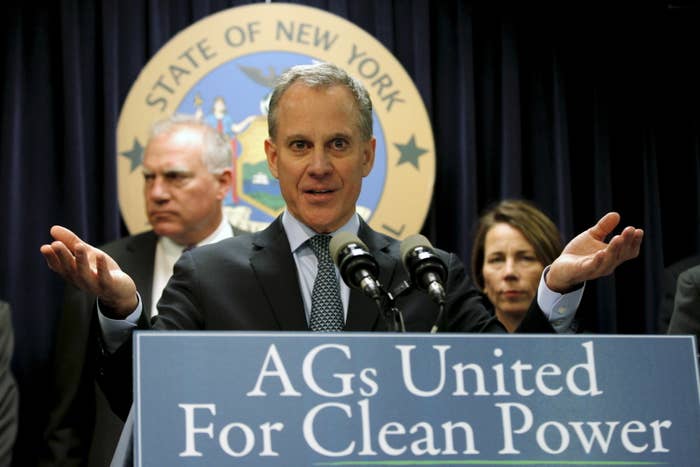

In March, attorneys general from 18 states and U.S. territories announced they would investigate Exxon for possibly misleading investors about the risks of climate change. That could count as securities fraud, according to New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

The attorneys general cited 2015 reports by the Los Angeles Times and Inside Climate News that suggested the firm’s leadership had for decades denied global warming’s reality, despite its own research confirming that climate change was caused by burning fossil fuel.

This investigation, pursued primarily by Schneiderman and Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey, “threatens to stifle genuine scientific debate about climate change,” House Science Committee chairman Lamar Smith said at a news conference announcing the subpoenas (which he has threatened since May). “The actions of the attorneys general amount to a form of extortion,” he added, saying the investigation was essentially a shakedown of Exxon, which has $269 billion in annual revenue, by cash-strapped states.

“The American people will wake up tomorrow shaking their heads when they learn that a small group of radical Republican house members is trying to block a serious enforcement investigation of potential fraud at Exxon,” a New York Attorney General spokesperson Eric Soufer, said in a statement on the subpoenas.

The subpoenas demand that the committee members receive all communications between the attorneys general and eight environmental groups — which include the Union of Concerned Scientists, Greenpeace, and the Rockefeller Family Fund — concerning the investigation. They also demand all of the internal communications among investigators related to the investigation.

Smith argues that the investigation into past scientific certainty at Exxon will cast a chilling effect on future research done by corporations into potential risks from their products, and block them from expressing corporate opinions on scientific matters. He called the investigation “a blatant effort to stifle free speech.”

Fraud, however, is not protected by free speech, Schneiderman said. Otherwise, companies could lie blithely about their products’ risks without fear of liability. New York’s attorney general has extensive power to investigate stock fraud, as well, where firms are supposed to warn investors about risks to their stock prices. In this case, that would mean warning stockholders that global warming could undermine the value of oil reserves.

Exxon, for its part, said it accepts the reality of climate change, and denies the suggestion that it misled investors. In a March statement it called Schneiderman’s charges “preposterous.”

New York Attorneys general, however, have cast a wide net in investigations into stock fraud in the past. For example, a 2002 settlement led to large investment firms agreeing to keep their banking and research arms from collaborating.

“While there is some doubt from legal experts about the efficacy of Schneiderman’s and the others’ case against ExxonMobil, I am in more doubt about Lamar Smith’s ability to obtain documents from the Attorneys General,” Colin Provost, a legal scholar at University College London, told BuzzFeed News by email. “The Attorneys General right to investigate has generally upheld in the past.”

The only similar case came in the 1990s, Provost added, when Mississippi’s governor, Kirk Fordice, sued his own state's Attorney General to stop him from proceeding with litigation against tobacco firms for misleading consumers about the cancer risks from cigarettes. “Fordice lost the case,” Provost said. “The tobacco litigation proceeded and you know the rest.”

The shadow of the $206 billion 1998 tobacco settlement between the once-powerful cigarette firms and states hangs heavy over the Exxon investigation. Twenty Democratic senators have spent this week denouncing fossil fuel firms for past financial support of climate doubters, in a “web of denial” publicity campaign making a comparison with big tobacco.

“Smith is attacking the free speech rights of organizations like ours with his subpoenas,” Ken Kimmel, president of the Union of Concerned Scientists, told BuzzFeed News. The group has provided government investigators with publicly available research on climate and on how fossil fuel companies fund critics of climate science, Kimmel said. “It’s not an illegal activity to complain about a corporation.”